Transcript of an interview between Miriam Bellamy, director at Whole Family Neurofeedback, and Dr. Michele Borba, an educational psychologist and best-selling author.

===

Miriam:

Hey, neurofeedback moms! I am Miriam Bellamy. I am the mom who started this group, and I am a licensed marriage and family therapist. And I am the director of Whole Family Neurofeedback. One of the many benefits of being a neurofeedback mom is that we bring you some of the world’s leading experts on topics that you care about.

So today, I am very happy to welcome Michele—Dr. Michele Borba. She’s an educational psychologist. She is a sought after motivational speaker. She has spoken in 19 countries on five continents. You must love to be on an airplane.

Dr. Borba:

No, but I love the people. It’s getting off the airplane that’s exciting. [laughs]

Miriam:

Yes, that drives us… She’s a consultant to hundreds of schools, corporations, including Sesame Street. She’s a regular NBC contributor. She offers realistic, research-based advice culled from a career working with over 1 million parents and educators worldwide. She lives in California. She has three grown sons.

Before we get started with asking Michele questions, I want to invite you moms to ask your questions throughout the broadcast. I’m actually just going to keep track of them, and then Dr. Borba’s giving a basic kind of presentation, then we’ll dig into those questions. So please at any time, throw them in the comments and I’ll make note of them.

So welcome, Dr. Borba. We really appreciate you being here.

Dr. Borba:

Oh, you are so welcome. Thank you for the invitation.

Miriam:

I can already tell this is going to be fun. We had some fun backstage, which is why we’re a little late, but that’s okay.

Dr. Borba:

It was fun. It’s all right. And boy, do we need fun, right?

Miriam:

Yes. Amen to that. So let’s start with me asking you, where did you get your start in this?

Before I go too far, she is the author of Unselfie, talking about empathy in this generation that we’re raising. And then she’s just come out with a book called Thrivers, as you can see there in the top banner “Raising Thrivers.” We’re gonna be talking about that today. How did you get your start in this work?

Dr. Borba:

101 was—the best thing I ever did was become a special education teacher. I learned more about what kids need from those students and their parents than I did in any textbook I ever read. I got my master’s in learning disabilities. Then I went out and got my doctorate in educational, psychology, and counseling.

And I’ve always been wondering one question. And that was, “Why do some kids struggle and others thrive?” So the most amazing thing is… I graduated from Santa Clara university, but UC Davis was where I really got the beginning of it all because there was an incredible researcher named Emmy Werner. And what she did was to look at cohorts of children who are facing extreme adversity… we’re talking sexual abuse, poverty, war zones, homelessness… and she kept looking at the same kids for 40 years.

And she found that, lo and behold, many of them were thriving despite the adversity. Once I saw that and other science that backs… that says resilience is learned; they’re not born with it; it’s not locked into your DNA… It’s been 40 years of writing Thrivers to figure out which traits matter most and what we can do to help all kids thrive.

And the best news is this is teachable. It’s simple. It doesn’t take a tutor or a program. It’s just weaving it into daily family lessons, experiences, chances. We just need a roadmap.

Miriam:

Okay. Wonderful. So you have a graphic here. Do you want me to switch to that?

Dr. Borba:

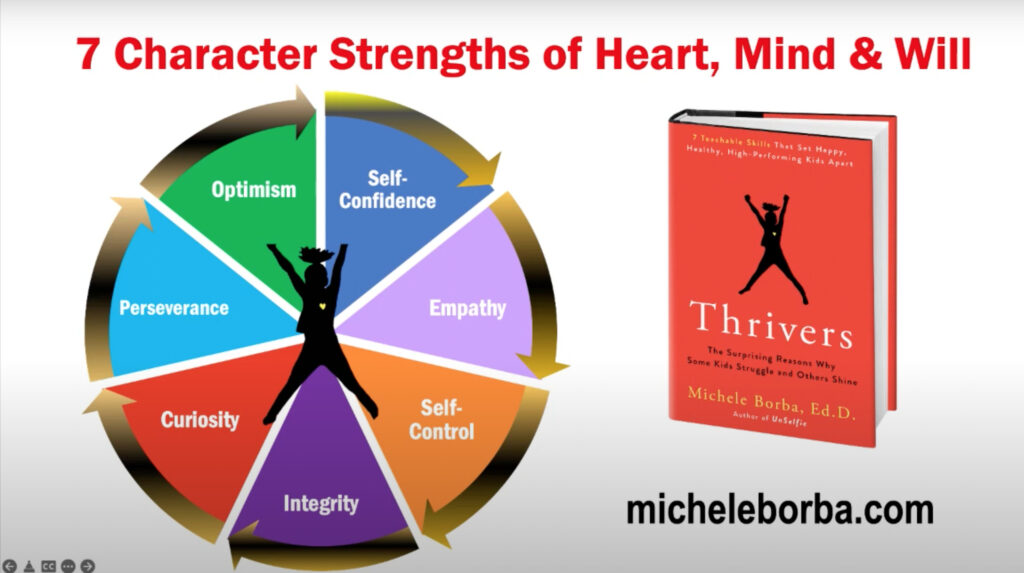

I’d love for you to switch to it just so you can all see, moms, that what I began to look at was… which are the strengths that are teachable, that seem to matter most in children’s resilience, as well as mental health needs.

And I found something that was fascinating. Of all the research and dozens of pieces that have come out, seven traits seem to matter most. So I’d just like to take a moment to share them with you. Each chapter in Thrivers is one of those seven traits, but it has also dozens of—why you need to teach it, and the strategies you can use. So self-confidence I think is the bulk that most of you are looking at right now.

I’ve been doing focus groups with kids across—In fact, I just got back from Abu Dhabi, and tomorrow I’m speaking with Africa. But no matter where I am, many of the kids are saying that the trait that seems to be the one that they’re nosediving right now is confidence. And that would make sense because when you’ve spent two years of wondering what the heck is going on… and you’ve been pacing and really taking all of your accolades based on your GPA and all of a sudden that trundles… what are you going to do?

So the piece that I think is really important is to maybe take this week, and look a little closely at your children… look at which things they seem to be more interested in. What drives them? What gives them passion? When are they a little more eager? And what we discover is that, back to Emmy Werner, is the children who are resilient almost always have a hobby.

They have something they can backlog on and it helps them decompress. I think we overlook that. I surveyed a lot of kids asking them “What’s your hobby?” and they looked at me dumbfounded. Who’s got time for a hobby? It makes no difference what the hobby is. And don’t go raising a white flag and feeling guilty if a kid doesn’t have one. Now’s the time to start introducing them.

You could simply say okay this week we’re going to do baking, or next week we’re going to do some knitting, or the following week let’s listen to music. See what gravitates around your child. That’s the key.

Let me give you one story. As my special ed background 101, I had one little guy in my classroom. You always have a child that till your dying day, you’ll never forget this kid. And mine was Michael. I taught up in Northern California and this child was in my room with severe learning disabilities. He also had a tough home life, but he also had apparently a very high IQ. And it was not materializing in the classroom at all.

His confidence level was just tanking. So I kept looking for “What is this kid good at?” He was around six at the time. I couldn’t find anything. And here’s the thing when a child is so, so low in confidence, if you find that thing that he’s good at, watch out. Because chances are he’ll rip it up, and he won’t buy into it. You have to be slow in helping a child begin to understand… “Here’s your strengths. Strengths are what’s going to help sustain you.”

So one day, Michael forgot to cover up the fact he was artistic or that he liked to draw. And here’s my point to you. I decided to keep my mouth shut because if I’d said, “Wow, Michael, you’re really good at that.” I know he would have covered it up. Because he was so, so low in it… in that feeling of I’m good at anything.

But it was also my moment—your moment, mom—to be able to start looking, to see, “Where are some other ways that I could help this kid shine or show that particular strength?” And so I had… I’m not so good at art… I had other moms come in and do some little lessons. I had particular moments for him and all the rest of the kids to do a little more art.

And then it was several weeks later, never ever happens overnight, he forgot to cover up the fact he was artistic and loved it. I happened to walk by and quietly leaned down and said, “Michael, that’s really good, and you seem so happy at it. Do you mind if I put it on the good work board?” I always ask permission.

And I put it on the good work board, and I’ll never forget it because three of the kids walked over to the board, looked at the art and turned and said, “Wow, Michael, you’re really good at art.” And the shine on that kid’s face was just extraordinary. And what began to happen is he showed the skill a little more.

But here’s the other pieces along the way. First, it took a long time. New behaviors take a minimum of 21 days. Number two, you’ve got to give him concrete ways to slowly start just experiencing his strengths and not his weaknesses. Third is I passed it on to other people. I’d have a conference with the mom and tell them, “This is what your kid is good at.” If any other teachers saw that child, I’d say, “Michael’s really good at art.”

And then you lose them as the teacher. They go onto the next class, the next class, the next. But I’ll never forget it because he went on to middle school. And at that time he was winning some art competitions. And then you don’t know what happens. And here’s my one moment in my entire career that said “Wow, Michele, I’m so glad you were a teacher”… that’s like the pat on the back: I got a letter from him years later.

And it just said, “Dear Mrs. Borba, I just wanted you to know I graduated from high school.” I literally almost fell to the ground because I didn’t know that was a possibility. And then he said, “And I got a scholarship to college. I’m doing exactly what I always wanted to do. I got it in art, but I also wanted you to know that I’m working for Disney Studios as an animator, and I owe it to you because you put my work on the good work board.”

So my point to you is don’t give up on the strengths. Don’t give up on the strengths. Find what your child is good at. That’s the beginning to thriving. The rest will come.

Miriam:

So part of what I’m taking from that is really watch this praising thing, right? You can’t just, if I heard you right, you can’t just sort of jump on this thing. Even a child without autism is going to be like… maybe have some kind of reaction to that. Is that, am I hearing you right?

Dr. Borba:

Yes, I am. You have to be very, very careful with it. We also learned that—Ohio State did a very interesting study that said it’s overrated.

We have gotten on the self-esteem bandwagon that says if we just praise and praise and praise and praise them, the rest will come and all will be well. No, it doesn’t. It just backfires, and it makes the kid very often more self-absorbed or needing our praise, to rely on us. Thrivers are made not born, and they almost always have agency… “I got this.” They’re not relying on, “Do I get a trophy for it?”

But a couple of other things you can do is you want to, when it comes to confidence, slowly help the child begin to acknowledge, or at least be aware of his or her strengths. Accept the weaknesses, because they’re also part of life. But another thing you can do is called “earshot praise.”

So what you do is your husband comes home and you recognize a natural, real strength about the child. You turn, without knowing that the child is there—he really is, and you know it—but you start praising the child to the husband. “Hey, you should see Ned’s art ability. He’s absolutely amazing. You would be so impressed with it.” And what happens is it quadruples the price. So little nuggets along the way.

The other thing is awareness of strengths. It takes a while. So you have to keep building them and building them. And it’s not a strength that is one that you are passionate about yourself. It’s who your child is. That’s very often the real stumbling block, realizing, “Oh my gosh, that’s not something I’m into.” So what? This is part of being a parent. Find what ignites your child’s passion.

Miriam:

So, what do you think sort of gets in the way of parents sort of letting their child, or figuring that out in their child, or seeing who their child is versus what they want them to be?

Dr. Borba:

I think that our, our culture has become so competitive. We’re so into education and push, push, push that it has to be what everybody else does. We worry about what the other child is doing. When in reality, we now know that if we really want to help the child—it doesn’t mean you’re going to stop with just the confidence level—but what I discovered on those seven traits, for instance, is that confidence has a multiplier effect.

If you start with at least knowing what you’re good at, or one thing that gives you… kind of allows you to decompress when push comes to shove, then you add another strength level or another. What actually happens is any two strains multiply…

What we also have been doing wrong, I think, is just going for well he just needs hope, or he just needs self-control. When in reality, any two of those multiply the outcome and become like superpowers to your child. So what you could do—in Thrivers for instance—is there is a four-page core asset survey of 150 strengths, like learning styles or modalities or verbal abilities or multiple intelligences.

[Miriam holds a sheet of paper] There you go. You can also get your own copy right there, that Miriam will give you a copy of. I just did this one for going to Dr. Phil on Friday. And what we did is we had a mom and her son that were really in a friction with each other, but I said, “You’ve got to stop pointing out all his weaknesses. Start figuring out what he’s good at.”

I could see instantly what happened was what the son who was a teen did his version of it. And then when mom did her version of it, they only agreed on five strengths. I’ve never seen anything so low.

Miriam:

So you’re saying they each did this core asset survey and only agreed on five.

Dr. Borba:

Yes, mom did it on her son. Son did it on himself. Then we put them together. That could be another option that you do, depending on the developmental level of the child. Everything is based on the child’s level and where you want to go from there, but we need a starting point.

Miriam:

Yeah. When I was looking at it, I was sort of thinking I should have my husband fill this out for me or me for him. [laughs]

Dr. Borba:

I don’t have the confidence to do that Miriam. That’s really good! [laughs]

Miriam:

I’ve been in a marriage therapist and family therapist for almost 25 years. And sort of thinking about what, what does get in the way of parents being able to see their kids? I think also family stressors, like marriage stress, right?

So I was talking to a mom about a month or so ago. She was doing something with her child. It sounded really smart and really well done. But all of a sudden she’s posting, like, “Did I do the right thing?” She was really unsure. And I knew because of my experience… and there was a piece of her story that got her husband involved or that he came in or whatever… when our husbands get anxious about our kids, they come in and say, “I don’t know. Should you be doing that or this?”

And then we get anxious and then we doubt what we’re doing with our kiddos.

Dr. Borba:

Exactly. Exactly. Well, it’s a high-stress job, this thing called parenting, because we want to do it right. So, I know, isn’t it? And we just add piles and piles and piles onto more and more things we’re supposed to do. That’s the first reason why I wrote Thrivers is I wanted to just look at what the science says are the simplest things we should be tuning into to maximize our results, that is really clearly evidence-based. So I think that’s core.

The other thing you pointed out as a really interesting point, too often we react and not respond. So we can really figure out, you know, what is our new game plan? And don’t add too much to the plate. Just one little thing. And pass it on to maybe grandma or the teacher. If we all do the same little thing, and we’re all reinforcing the same little thing, we’re going to maximize the results and change the results a lot faster.

Sometimes it’s 21 days and sometimes it’s 7 years. It’s however long it takes for what you think is going to matter for your child.

Miriam:

I love that you brought grandma in, because it might not be our husband or wife. It might be our mother, our father coming in and making comments. And I’m sure they don’t mean to make us anxious, but anxiety flows through the system.

Dr. Borba:

Does it ever.

Miriam:

Yes it does. So let me think about this. I wanted to ask you… talk to me a little bit about your book UnSelfie, where you really sort of talk about empathy. As a family therapist, I do work primarily with adults. I see, for example, too much empathy and women who tend to get really, really sensitized and in tune with everybody else’s pain. Can you speak to that when we’re encouraging empathy?

Dr. Borba:

Yeah. Let’s talk about that. Well, it’s also with kids, highly empathetic kids. We have got to give them permission to step back. You can’t solve the world’s crisis-weighty pie. And so that’s a piece of it. Notice that [empathy] is the second [referencing the graphic], because social competence plays a huge piece in mental health and resilience.

And now what we know, as Emmy Werner would say, social competence also plays a huge role in helping kids bounce back. And what’s happening right now with all the physical distancing, many of our children—I don’t know about any listeners here—their kids are feeling a little more socially anxious. They’re feeling a little more separation anxiety.

So key number one is, here’s what we know about empathy. We’re hardwired for it. and we need it desperately. But when stress builds and we don’t have a way to manage that stress level, what happens is we have to dial our own empathy down. And if we don’t, burnout is the outcome.

So one piece of this, Miriam, is burnout has hit us all, because the things that we needed most was the person next door, or a girlfriend or somebody to be networking with that’s not there. The second thing is we are seeing such dismal dismal news, and our heart is breaking. I mean, if you watch the war zones, what’s going on in Ukraine, after a while, it’s like, you just are sobbing yourself.

So the second thing is you gotta be careful. Because you’ve got to turn that off so that you can be in control with your own children. Third thing that I love is what you also said… There’s some of us out there that are highly empathetic, and if you’re not careful, you try to take on the world.

And the best comeback I ever saw with that was Mother Teresa. Mother Teresa—miss empathy one—said, “If I kept looking at all those photos of the starving children, I would never be able to think or work. So what I don’t do anymore is look at the masses. I just look to one and I try to solve and help the one.”

If we put that maybe as our perspective, I can’t do it all, but I’m just going to go right now with my family or that one child, it’ll help give perspective so that we have more compassion for ourselves. And that’s what we need right now is self-compassion to manage the stress, so it doesn’t spill over to our kids.

The new research is saying that our stress is higher than our children’s right now. And rightly so, rightly so. So let’s look at and realize that’s also going to impact not only our job performance, our relationships, but also our parenting.

Miriam:

So I have a child—I’m going to get some personal advice here—I have a child who’s almost 18 and super empathetic and sensitive and that kind of thing. And she’s very worried about other people’s feelings. She says “I’m sorry” a lot. It gets a little annoying. [laughs] What do you say to a child who’s that… well you were saying, you know, how you had to turn it off. How would you help a child, even an older child, to turn it off?

Dr. Borba:

One thing that I’ve discovered that is actually a term called “altruistic suffering.” That is one of the best things for your daughter. And that is when she sees someone’s pain, she takes it in—oh glories that she does—but if she keeps taking it in and keeps taking it, it can be overwhelming to her. So what I’ve seen that many teens are now doing is finally realizing, “I can’t keep taking them. So I’m going to give it back.” And instead of getting, if you give back, it’s the best stress reducer there is.

Example. A group of kids from Glenbard High School were so concerned about some of their friends—who during social distancing, they couldn’t see the person they needed most with their own mental health needs, which is a school counselor—and they were really worried about those friends of theirs.

So what they did is they put together a little chain of, “Here’s the kids we worry about.” And then—”We kept social distancing, Dr. Borba, but we did it all in our own homes.” They figured out that… they went to their strengths. What is each of us good at? I’m good at baking cookies. I’m good at writing a note. I’m really good at decorating a card.

So what they did is that every day they made a driveway drop-off bag. One kid would drive it off. The other kid would bake the cookies. The other kid would write the handwritten note to the child, and everyday it was to a different child.

And I said, “How’s it going?”

They said, “It’s absolutely unbelievable. We were so stressed and worried about our friends, but now what happens is every single day, the kid we drove and dropped it off to calls us sobbing and thanking us because they didn’t think that anybody cared. And now we saw, and we got to do it again. It’s the best thing that we ever could have done is helping somebody else because it helps us, too.”

Miriam:

You kind of get out of your own world and get into the world.

Dr. Borba:

Now the key is, is that you got to do stuff that is meaningful to the child and age-related to the child. Not, “It’s going to look good on a college resume.”

So example about another kid who came home really worried about the neighbors next door. And bless the mother because she said, “Well, what are you worried about?”

“I’m worried. She’s all by yourself. She’s 80, mom. She’s really lonely.”

And then the mother said the best question ever. “What can you do? What can you do to help her?” And you realize she used to love the Christmas cookies that we dropped off. “So why don’t we bake some more Christmas cookies mom?” But even now we could do it, like spring cookies.

“Good idea.” And the child dropped it off. The response was unbelievable because when the lady opened the door, the tears of joy, the child said, “We’ve got to go make some more cookies, mom. Maybe the other neighbors need it, too.” The mom said it was such a relief to that child. And it helped him realize he could do good.

That’s building that identity, and that confidence level is also piece and parcel, because now when he knows that he did good, his agency goes up. He’s got his confidence level moving up.

And it could be simple little things, like all the kids during COVID who, the teens that got worried about their younger brothers and sisters, so they made sidewalk chalk drawings all over. And pretty soon half the kids in the neighborhood joining in and doing sidewalk chalk drawings, but they said, “It made us feel good just as much as it made our five-year-old brothers and sisters feel good. So we got to keep doing it.”

Miriam:

Nice. So I want to go back to something you said just real quick. So I’m going to share the screen one more time. These are these core strengths, character strengths that can be trained. Did I hear you right where you said, if you develop two of them, that there is kind of a cascade effect?

Dr. Borba:

Any two has a multiplier effect. And by the way, it makes no difference what order it is. The next question to any mother, “Oh my gosh. Does he need all seven?” No, it’s a rare adult that has all seven, but if you look at those as your roadmap for the rest of your life—because that’s how long it’s going to take—it just keeps going and going and going.

And the other thing is you’ve got to make it—so whatever those seven are, you may want to start with, “Which does my child currently have?” Or the next thing is, “Which ones are my strengths?” Because you’re more likely to be modeling them. And then you take it so that you don’t make any assumptions.

Let’s go to empathy a minute, because one piece of empathy we know is that emotional literacy is the gateway to it. Kids have to be able to either identify emotions in themselves or others. And I remember being in Ohio when I was doing a book signing for Thrivers, and some teens came to me. And one kid—he must’ve been about 15—who was autistic, standing in front of me, wanted a book signed. And I was like, “Wow.”

I said, “How did you like the speech?” And he said, “Oh gosh, it was so good.” I said, “What made it so good?” He said, “Wait a minute. Wait a minute. It’s coming.” I said, “What’s coming.” And all of a sudden you saw him start to break out. He said, “It’s a joy bubble. I can feel it. I can feel it. I can feel it.” And then he completely broke down and started to cry. His mom and dad smiled. And he said, “I just felt so good.”

So it was… his parents had discovered that that was the term that he used—how wonderful—and he was able to tell them what his emotions were based on, “It feels like a joy bubble.”

Whatever it is, we gotta make it so it’s developmentally or just appropriate to that age of the child. And maybe start talking emotions far more in our own family. We do a better job, by the way, with our daughters at age 2 than we do with our sons at age 2.

Miriam:

Okay. Is there an optimal age to talk to boys?

Dr. Borba:

The optimal age is age 2. We just don’t talk to them. We did that… they put us in front of two way mirrors and they watched moms with 2-year-old daughters and with 2-year-old sons, and they found that of the two, we talk emotions far more with our daughters. “Oh, you look so happy,” or so sad, or so proud.

With boys it’s… “Boys don’t cry. You’re going to lose your friend if you do that.” And there’s already, by the age of five, a pink/blue divide in terms of emotional language and identification. So talk emotions naturally.

Start with a puppy, “How does Fido feel happy?” He does look happy, because his tail is going up and down. Or with the baby. The best program I’ve ever seen in my life is Roots of Empathy, that actually uses babies to come into classrooms once a month. And they use the baby—the kids adopt the baby for the year—every month to watch the emotional progression of a baby. How wonderful is that?

Miriam:

What’s the name of that program?

Dr. Borba:

Roots of Empathy. It’s absolutely mind-boggling. It’s one of the—each chapter in Thrivers has a story that is just extraordinary that I’ve seen someplace in the world. But 8,000 kids have been exposed to the program. It’s by Mary Gordon.

And what happens is that bullying goes down. Inclusion goes up. Emotional literacy goes up. And empathy goes up. It’s one baby all year long. Every month, the baby comes in. The little kids, when the baby comes in and sits down and the teacher says, “How does Clara seem to feel today?” And the kids could read her language.

And then they turned to me and said, “Clara’s learning empathy.” [laughs] And I said, “I don’t think it’s just Clara.” It was the kids learning it. It was lovely, but it was concrete.

Miriam:

Yeah. And so speaking of concrete. Let’s go ahead and just wrap up for today, and with this idea of this core asset survey, because as you said… for a mom or dad, who might be listening, to begin to think about these… seven traits. Should I call them traits?

Dr. Borba:

Usually strengths.

Miriam:

Strengths. Okay. Yeah. Traits would sound like it’s not teachable. Like it’s inborn, right?

Dr. Borba:

Yeah. Right. And it is teachable. At any age they’re teachable.

Miriam:

Yes. Yes. And assessing where your child is now, where you are now, where your spouse might be now… and building from there and keeping it simple.

Dr. Borba:

Love that. Keep it simple. There’s also a guide at the very beginning that you can do a quick little test if you wanted to. Or once you get to know those seven strengths… by the way I would never read the whole book at one slot. I would slowly just keep reading maybe one chapter at a time. And then each chapter is going to have dozens of ways to teach it age by age.

So find one thing, right. One thing. Teach it to yourself, and then teach it to your kids, and then keep practicing and practicing and practicing in those everyday moments till your kids can do it without you. Then add the next and the next.

Miriam:

That slow, steady effort—that is parenting.

Dr. Borba:

Isn’t it?

Miriam:

Thank you so much for being with us. Great to be with you today. All right. Thanks moms. And we will see you next time.